Early Postage Stamps

On July 1, 1847, the United States Post Office Department released its first two stamps, marking the beginning...

.png)

On July 1, 1847, the United States Post Office Department released its first two stamps, marking the beginning of what came to be known as the 47-year "Classic Period" of postage stamp production in the U.S. It was a period of experimentation with different techniques for printing, gumming, and perforating stamps. The very earliest stamps were not perforated, meaning that they had to be hand-cut from the sheet with a knife or scissor. The backs of stamps were gummed by hand, though later, machines would take over that task. Between 1847 and 1894, five different private banknote companies printed U.S. stamps, using a variety of different paper types. After 1893, the job of printing postage stamps became that of the United States Bureau of Engraving and Printing.

Despite the arrival of postage stamps, most Americans in 1847 still mailed their letters without stamps. It has been estimated that only one in fifty customers actually purchased a stamp for their mail. Stamp use went up somewhat in 1851, when the Post Office Department modified its rates so that prepaid letters cost 3 cents, while postage for the same letter cost 5 cents if paid by the receiver. The requirement that postage for all letters be prepaid was implemented on April 1, 1855. Beginning on January 1, 1856, all letters were required to have postage stamps on them.

The earliest stamps are known as Regular Issues (to distinguish them from other kinds of stamps that were later printed, such as commemorative issues).

.jpg)

America's first two postage stamps, the 5¢ Benjamin Franklin and 10¢ George Washington, were designed and printed in 1847 by the New York City banknote engraving firm of Rawdon, Wright, Hatch & Edson which had produced the New York Postmaster Provisional stamps earlier. Operating under a four-year contract, the company engraved the initials "RWH&E" at the base of both stamps that it printed. This can easily be seen in the stamps today, sometimes requiring magnification. Although Rawdon, Wright, Hatch & Edson produced only two different stamps (another company won the second printing contract in 1851), the quality of their designs set a standard for future postage stamp releases. The designs for both stamps had been made years earlier by the noted painter, Asher Brown Durand, originally for use on banknotes.

The production process began with engraving a precise image, in reverse, onto a steel die. A band of softer steel, called a "transfer roll", was rocked over the die to produce an impression of the image. The transfer roll was pressed onto a printing plate, producing multiple reverse images. That plate was then used for printing the stamp. Both denominations were printed onto a thin bluish wove paper in sheets of two side-by-side panes of one hundred stamps each. The dies used for printing the first two postage stamps were not made especially for them, but were ones that happened to be in stock, having been used previously for printing bank notes.

Both stamps were put on sale at the New York City Post Office on July 1, 1847, and they arrived for sale at the Boston post office on the following day. Other post offices were supplied during the month of July. The first person to purchase a pair of 1847 stamps is believed to have been Congressman Harvey Shaw of Connecticut, who kept the 5¢ stamp for himself and presented the 10¢ stamp to his state governor. Once used for posting a letter, a stamp was meant to be cancelled. Postmasters at the larger post offices received an official cancellation hand-stamp with a circular, seven-bar enclosed grid. Smaller post offices were expected to cancel each stamp by hand, with an "X" in pen, but many obtained unofficial hand stamps, or even custom-made their own.

The 1847 Regular Issue stamps were only used for four years. During that time, postal rates were 5¢ for letters travelling fewer than 300 miles, and 10¢ for letters going farther. On July 1, 1851, new postal rates (along with a new issue of stamps) rendered the founding pair - both the 5¢ Franklin and 10¢ Washington - obsolete. After that date, neither stamp was accepted for postage. This event was one of only two instances in U.S. postal history that stamps were demonetized; the second was at the beginning of the Civil War, a decade later.

The specific stamps selected for focus in this section are simply to illustrate how American patriots came to be commonplace on U.S. postage. The Classic Period of United States stamps features 47 years including reprints of previous stamps, reuse of the same image on different stamps, multiple varieties of many stamps, varying colors of the same stamp, five separate printing contractors, a wealth of technological advancement and changes in postage rates. Innovations such as perforations and grilling came into being, one short-lived and one lasting. What didn't change very much at all was the subject matter: American founding fathers and patriots. The postage stamps of the Classic Period can be a fascinating foundation to any stamp collection and requires the expert guidance of a philatelic expert.

.jpg)

General Andrew Jackson had initially been considered for the honor of appearing on the nation's first stamp, but it was decided to recognize America's first Postmaster General, Benjamin Franklin, instead. Franklin had been appointed by the Second Continental Congress in July of 1775, and served until November of 1776. The 5¢ stamp features an image of Franklin based upon a painting by James Barton Longacre. The stamp itself has a colorful past. Although generally described as printed in light brown ink, there are actually more than 25 different color shade classifications for this stamp. While some shades are fairly common, others are quite rare.

.jpg)

The 5¢ Franklins also changed in appearance from one printing to the next. The stamps were printed on five separate occasions, with the first printing being the sharpest. Each time the stamps were printed again, a fuzzier image resulted due to abrasion caused by earthen pigments in the brown ink that was used. By the third printing, the image had become quite blurry due to residual ink on the plate. The plate was then acid-etched prior to the fourth and fifth printings, making deep lines sharper while fine lines almost vanished. There is sufficient literature available that a skilled observer can identify which printing a particular Franklin stamp comes from. Over the span of the five printings, about 4.4 million of these stamps were produced and about 3.7 million sold. As America's first official national postage stamp, the 5¢ Benjamin Franklin ranks highly with almost all collectors of U.S. stamps.

.jpg)

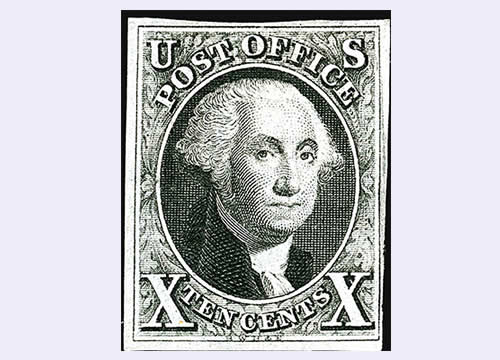

George_Washington_1847_issueThe 10¢ Washington stamp image was based on a portrait by Gilbert Stuart. It is unusual among U.S. postage stamps because the denomination on the stamp is given in Roman numerals. There are fewer variants of this stamp than of its 5¢ counterpart. A non-abrasive, carbon-based black ink was used and the printing plates did not become noticeably damaged with time, so all four printings of this stamp are nearly identical. The stamp does not exhibit an extensive range of color shades. Some postmasters complained about its black color, however, because it made cancellation marks difficult to see. Relatively few of these stamps were printed - about 1.05 million in all. Of that number, about 863,800 were sold. The 10¢ George Washington is also a favorite of most collectors of U.S. stamps.

About 100 of the currently existing 10¢ Washington stamps have been bisected, or cut in half, often on the diagonal. This was done so that the stamp could be used in place of two 5¢ stamps. Most likely, this was permitted in order to use up the remaining supply of 10¢ stamps prior to July 1, 1851. On that day, both 1847 stamps were officially demonetized, and no longer valid for sending mail. Nevertheless, about 50 examples of invalid uses of this stamp after that date are known.

In 1851, new postal rates went into effect to encourage the public to use the federal postal system more. People could send a letter ten times the distance for 40% less than before. Along with the reduced rates came the need for new stamps. A six-year printing contract (later extended to 1861) was awarded to Toppan, Carpenter, Casilear & Company. All stamps in this series were produced in both perforated and imperforate formats. They were designed by Edward Purcell, with vignettes most likely engraved by Joseph Pease. Two of them - the 3¢ and 5¢ - are bordered by intricate scrollwork, engraved by Cyrus Durand with a geometrical lathe he had invented. Because all the stamps in this series had complex border designs and were printed with several tones of ink, there is considerable variation in the printed stamps.

.jpg)

Printed in indigo blue ink, the 1¢ stamp again features Benjamin Franklin, based on a bust by Jean Jacques Cafferi. A penny was the newly-established rate for "circulars" (junk mail). This stamp was printed several times, in sheets of two hundred, over ten years. Beginning in 1851, the stamp was released as imperforate; perforations were added in 1857. The ornate edges of this stamp caused printing difficulties, particularly with the top and bottom edges. The stamp is classified into many types and varieties (and Scott Catalogue numbers) according to the relative completeness of the border design. The stamps with intact borders, assigned Type I, are the rarest among the imperforated specimens of this stamp. Type V, the most common, has incomplete borders on all four sides. The 1¢ Franklin has been called the most studied stamp in history and some philatelists collect and concentrate only on the varieties of this stamp.

.jpg)

On March 3, 1851, the cost for mailing single letters was reduced from 5¢ to 3¢, making the Washington stamp the most commonly used of the 1851-57 issue. The design shows George Washington in profile, from a 1785 terra cotta bust by Jean-Antoine Houdon. Over its ten years of use, the 3¢ Washington was printed in various shades of orange and red and had minor design changes. Most stamps issued were printed on white wove machine-made paper. Like the 1¢ Franklin, this stamp was printed without perforations until 1857. The color diversity, subtle design variations, and presence or absence of perforations have resulted in many collectible varieties.

.jpg)

Featuring a design based on a portrait by Gilbert Stuart, the red-brown 5¢ Jefferson was the first U.S. stamp to celebrate the third President. Unlike the other stamps in this series, it was not issued until 1856 (in imperforate form). The following year perforations were added, and more than 2.3 million perforated stamps were eventually issued. The stamp's value gave it few domestic uses; instead, it was likely intended to cover the U.S. Internal Rate for British packet ships transporting mail between the United States and England. Applied to an envelope in strips of three, it was often used to send a letter to France.

.jpg)

According to the Postage Stamp Act of March 3, 1855, postage for letters travelling more than 3,000 miles was raised to 10¢, making a 10¢ postage stamp an urgent necessity. The dark green 10¢ Washington was issued on May 12, 1855. The design was based on a portrait by Gilbert Stuart. The frame and lettering were engraved by Henry Earle. Design variability and the presence or absence of perforations resulted in many variants of this stamp and five recognized types. More than 5 million imperforates were printed, and 16 - 18 million in the perforated format. This stamp was often used for sending a letter across the country from coast to coast.

.jpg)

When the 12¢ Washington was released on July 1, 1851, it had the highest value ever printed on a U.S. stamp up to that time. The image came from the same Gilbert Stuart portrait as the 10¢ stamp, but it was printed in black ink. Because 12¢ covered half the regular rate of a letter to England, it was often used in pairs. About 8.3 million were printed, of which 2.5 million were imperforate and the remaining 5.8 million perforated. Like the 10¢ George Washington stamp of 1847, this 12¢ stamp suffered being bisected vertically or diagonally, to cover the 6¢ postage rate. Soon, however, the Post Office Department outlawed bisected stamps.

In 1857, when the Post Office Department began perforating stamps, all the designs of 1851 were re-released in the new perforated format and an additional three designs were added.

After the outbreak of the Civil War (1861), the government declared existing stamps invalid for postage and quickly issued redesigned stamps. The designs of this series are similar enough to the old designs to be familiar, but still easily distinguished. These are the oldest United States stamps still valid for postage.

Between 1867 and 1871 the Post Office Department applied embossed impressions to its stamps in a process referred to as "grilling". The function of the grill was to make it more difficult to wash off cancellations in order to reuse stamps. The extent to which reuse of stamps was an actual problem is not clear. The first grills covered the entire stamp, but later examples only cover part of the stamp. Depending on the condition of the stamp, a grill can be difficult to see and study. Grills are distinguished by the size of the embossed area and by the number of "points" in the grill.

Following the short run of the 1869 Pictorial Issue, a new series of more traditional portraits was released by the National Bank Note Company in 1870, ushering in a period of stamp production collectively called the Banknote Era. During this time numerous similar-appearing stamps were produced as contracts changed hands among three printing and engraving contractors. Stamps varied by paper type and grill, but also by a series of intentional plate variations known as secret marks. While there are some examples available, stamps of this era are some of the most scarce and sought after in all of philately.

.jpg)

.jpg)

When the Continental Bank Note Company took over the printing contract in 1873, it took over many of the original plates and dies of its predecessors. The designs are, therefore, similar or identical to those printed earlier. The 1¢ through the 12¢ can be identified by "secret marks" added to the designs. The 15¢ can be distinguished by plate wear and shade variation, and the 30¢ and 90¢ can be distinguished by shade differences. Although both National and Continental printed the 24¢ stamp, there is no way to tell the issues apart; there is no secret mark or consistent color variation. There is one exception: a single example of the 24¢ exists on ribbed paper which was only used by Continental.

The National, Continental and American Bank Note Companies ultimately merged under the name of the American Bank Note Company which assumed the contract for printing stamps in 1879. When American first took over the contract, it used the Continental plates. The original plates were imprinted Continental, so the imprint on these issues does not always accurately reflect the printing firm. The American stamps are distinguished from the Continental printings by paper type. American used paper that is described as "soft porous." When held to a light, soft porous paper looks mottled or quilted.

The American Bank Note Company re-engraved several denominations in 1881. The stamps printed on soft porous paper can be distinguished from the earlier printings by subtle design changes.

In 1883, the domestic letter rate was reduced to 2¢ per one-half ounce. To accommodate the change two new stamps were issued: the 2¢ Washington (red brown) and 4¢ Jackson (blue green). In 1887, the 1¢ Franklin was redesigned with a frame similar to the 2¢ and 4¢ stamps.

1890-93 marked the last regular issue stamps printed by the American Bank Note Company. Although similar to previous issues, they are smaller and different in their shades of color, introducing the look and style of U.S. definitive stamp issues for the next 50 years. The Bureau of Engraving and Printing, a part of the U.S. Department of the Treasury, was about to take responsibility for producing American stamps.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

A Hobby of a Lifetime!

On July 1, 1847, the United States Post Office Department released its first two stamps, marking the beginning...

In March 1869, the Post Office Department issued a set of ten stamps that broke from convention. While the faces of...

1893 marked nearly the end of the Gilded Age (1870 - 1900), the early...

The transformation of the United States from an agricultural to an increasingly industrialized and urbanized society brought about...

More1901 found the U.S. still in the Progressive Era (1890s-1920s), a time of intense social and political change in American society...

MoreThe United States was well into the Progressive Era (about...

With the assassination of President McKinley at the Pan-American Exposition in 1901, Vice President Theodore Roosevelt, not quite 43...

MoreThe Gilded Age and the first years of the 20th century were a time of great social change and economic growth in the United States...

MoreThe United States was far into the Progressive Era by 1915 and many of its ideal reforms had been implemented or soon would be...

MoreWhen war exploded across Europe in August, 1914, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson made a decision...

MoreThe 1920s were an age of dramatic social and political change. For the first time, more Americans lived in cities than on farms. The nation's...

MoreStamp Collecting can be challenging and rewarding at the same time. Our job is to make you feel comfortable and prideful about your collections.

CONTACT USCopyright (c) MiniatureArtWorksUSA.com - All Rights Reserved.