Born in Boston in 1706, Benjamin Franklin left school at age 10 to work in his father’s candle shop. In 1718, Franklin apprenticed to his brother James, a printer and founder of Boston’s New England Courant. Franklin read voraciously, contributed anonymous articles to his brother’s newspaper, and managed the paper while his brother was imprisoned for a political offense. At 17, Franklin ran away and ended up in Philadelphia, where he found work as a printer. Franklin started his own print shop by 1728 and purchased The Pennsylvania Gazette. His wildly successful Poor Richard’s Almanack secured his fortune.

Franklin was appointed postmaster of Philadelphia by the British Crown Post in 1737. Newspaper publishers often served as postmasters, which helped them to gather and distribute news. Postmasters decided which newspapers could travel free in the mail — or in the mail at all. Postmaster General Elliott Benger added to Franklin’s duties by making him comptroller, with financial oversight for nearby post offices. Franklin lobbied the British to succeed Benger when his health failed and, with Virginia’s William Hunter, was named joint postmaster general for the Crown on August 10, 1753. Franklin surveyed 1,600 miles of post roads and post offices, introduced a simple accounting method for postmasters, and had riders carry mail both night and day. He encouraged postmasters to establish the penny post where letters not called for at the Post Office were delivered for a penny. Remembering his experience with the Gazette, Franklin mandated delivery of all newspapers for a small fee. His efforts contributed to the Crown’s first North American profit in 1760.

In 1774, judged too sympathetic to the colonies, Franklin was dismissed as joint postmaster general. In 1775, Franklin served as a member of the Second Continental Congress, which appointed him Postmaster General on July 26 of that year. With an annual salary of $1,000 and $340 for a secretary and comptroller, Franklin was responsible for all post offices from Massachusetts to Georgia and had authority to hire postmasters as necessary.

Two postmasters became U.S. Presidents later in their careers — Abraham Lincoln and Harry Truman. Truman held the title and signed papers but immediately turned the position and its pay over to an assistant. Lincoln was the only President who performed the actual job as a postmaster. On May 7, 1833, 24-year-old Lincoln was appointed postmaster of New Salem, Illinois. He served until the office was closed May 30, 1836. The United States Official Register, published in odd-numbered years, dutifully records A. Lincoln as receiving compensation of $55.70 in the 1835 volume and $19.48 for one quarter’s work in the 1837 volume. Besides his pay, Lincoln, as postmaster, could send and receive personal letters free and get one daily newspaper delivered free. Mail arrived once a week. If an addressee did not collect the mail, as was the custom, Lincoln delivered it personally — usually carrying the mail in his hat. Even then, Lincoln was "Honest Abe."

The Post Office Department, the communications system that helped bind the nation together, grew in the 19th century and developed new services that have lasted into modern times and subsidized the development of every major form of transportation. Between 1789, when the federal government began operations, and 1861, when civil war broke out, the United States grew dramatically. Its territory extended into the Midwest, reached down the Mississippi River and west to the Rocky Mountains after the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, and stretched to the Pacific coast by the 1840s. The country’s population grew from 3.9 million people in 1790 to 31.4 million in 1860. The Post Office Department grew, too. The number of post offices increased from 75 in 1790 to 28,498 in 1860. Post roads (roads on which mail travels) increased from 59,473 miles at the beginning of 1819 to 84,860 by the end of 1823. By 1822, it took only 11 days to move mail between Washington, D.C., and Nashville, Tennessee.

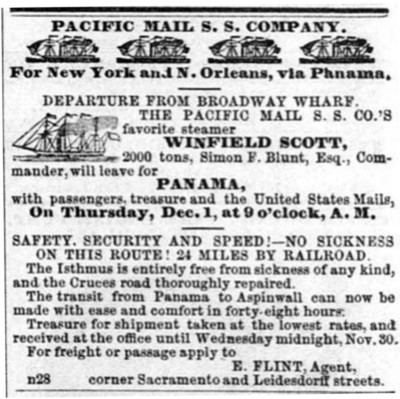

Steamboats: In 1811, cutting-edge technology met up with the nation’s mail system. Fast-moving steamboats began traveling the rivers, replacing packet boats, rowboats, and rafts as a means to carry mail. Beginning in 1815, operators of steamboats and other craft had to deliver mail they carried to local postmasters within three hours of docking in daylight or two hours after sunrise the following day. By the 1820s, more than 200 steamboats regularly served river communities and in 1823, Congress declared waterways to be post roads. Use of steamboats to carry mail peaked in 1853 prior to the expansion of railroads. Even before gold was discovered in California in 1848, the Post Office Department had awarded contracts to two steamship companies to carry mail between New York and California. The goal (often missed) was to get a letter from the East Coast to California in 3 – 4 weeks. Mail traveled by ship from New York to Panama, moved across Panama by canoes and mules, then went on to San Francisco by ship. Faster transportation to the Pacific coast was needed.

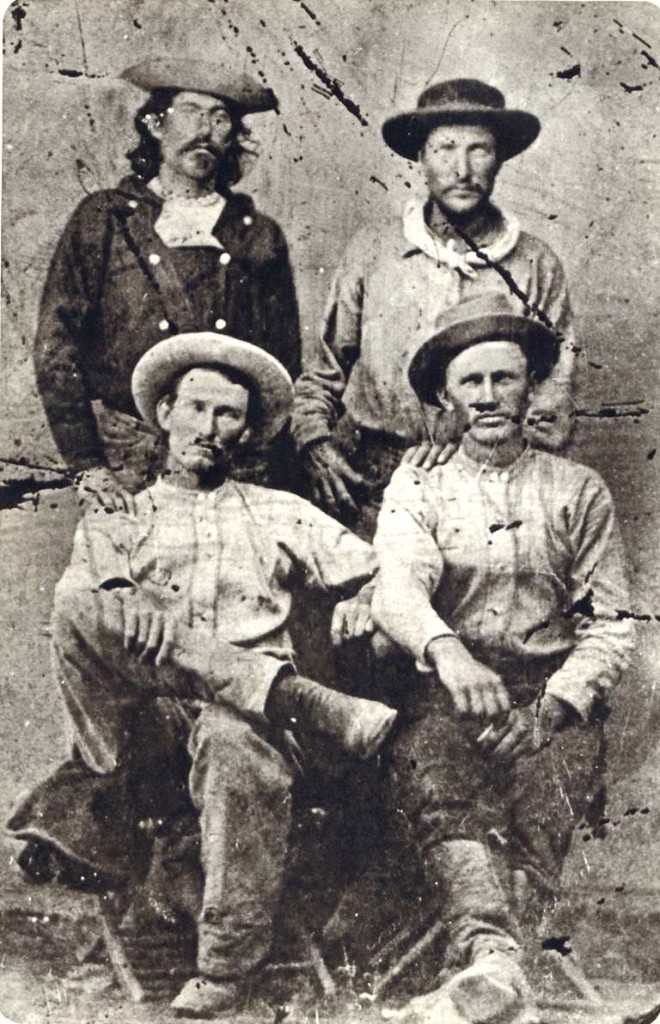

Pony Express: U.S. transportation pioneer William H. Russell advertised for hostlers and riders to work on the Overland Express Route via Salt Lake City in March, 1860. Russell had failed repeatedly to get the backing of the Senate Post Office and Post Roads Committee for an express route to carry mail between St. Joseph, Missouri — the westernmost point reached by the railroad and telegraph — and California. St. Joseph was the starting point for the nearly 2,000-mile central route to the West. Except for a few forts and settlements, the route beyond St. Joseph was a vast, unknown land, inhabited primarily by Indians. Many thought that year-round transportation across this area was impossible because of extreme weather conditions. Russell organized his own express to prove otherwise. With two partners, Russell formed the Central Overland California & Pike’s Peak Express Company. They built new relay stations and readied existing ones. The country was combed for good horses — hardy enough to challenge deserts and mountains and to withstand thirst in summer and ice in winter. Riders were recruited hastily but, before being hired, had to swear on a Bible not to cuss, fight, or abuse their animals and to conduct themselves honestly.

On April 3, 1860, the Pony Express began its run through parts of Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska, Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, Nevada, and California. On average, a rider covered 75 – 100 miles daily. He changed horses at relay stations set 10 – 15 miles apart, swiftly transferring himself and his mochila (a saddle cover with four pockets or cantinas for mail) to the new mount. The first mail by Pony Express from St. Joseph to Sacramento took ten days, cutting the overland stage time by more than half. The fastest delivery was in March, 1861, when news of President Abraham Lincoln’s inaugural address was carried from St. Joseph to Sacramento in 7 days and 17 hours. On July 1, 1861, the Pony Express began operating under contract as a mail route. By that time, the Central Overland California & Pike’s Peak Express Company was deeply in debt. Though it had charged as much as $5 a half ounce for a letter at a time when ordinary U.S. postage was no more than 10¢, the company did not make its operating expenses as it was losing as much as $30 per letter according to William Russell’s calculations. The Pony Express officially ended October 26, 1861, after the transcontinental telegraph line was completed.

Mail by the rails: Some three decades before the Pony Express galloped into postal history, the “iron horse” made its formal appearance. In August 1829, an English-built locomotive, the Stourbridge Lion, completed the first locomotive run in the United States on the Delaware & Hudson Canal Company Road in Honesdale, Pennsylvania. The next month, the South Carolina Railroad Company adopted the locomotive as its tractive power. In 1830, the Baltimore & Ohio’s Tom Thumb, the first American-built steam locomotive, successfully carried more than 40 people at more than ten miles per hour. This beginning was considered less than auspicious when, in late August 1830, a stage driver’s horse outran the Tom Thumb on a parallel track in a race at Ellicott’s Mills, Maryland. Later, however, a steam locomotive reached the unheard-of speed of 30 miles per hour in an 1831 competition in Baltimore. The Post Office Department recognized the value of the railways to move mail as early as November 30, 1832, when stagecoach contractors on a route from Philadelphia to Lancaster, Pennsylvania, were granted an allowance of $400 per year “for carrying the mail on the railroad as far as West Chester from December 5, 1832.”

An Act of July 7, 1838 designated all United States railroads as post routes, and railroad mail service increased rapidly. In June, 1840 two mail agents were appointed to the Boston-Springfield route, “to make exchanges of mail, attend to delivery, and receive and forward all unpaid way letters and packages received.” The route agents opened the pouches from local offices, and sent the balance to distributing post offices for further sorting. Gradually, the clerks began to sort for connecting lines and local offices, and the idea of sorting mail on the cars evolved.

Star Routes: Post riders on horseback were the first contractors to carry mail between post offices. In 1785, the Continental Congress authorized the Postmaster General to award mail transportation contracts to stagecoach operators. Despite their higher costs and sometimes lower efficiency, stagecoach proposals were preferred over horseback as a “superior mode of transport”. An Act of March 3, 1845, took steps to reduce mail transportation costs. Congress abandoned its preference for stagecoaches, with contracts to be awarded to the lowest bidder. These were known as “celerity, certainty and security” bids. Postal clerks shortened the phrase to three asterisks or stars (***). The bids became known as star bids, and the routes became known as star routes.

In 1845, more than two-thirds of the Post Office Department’s budget was for transportation. By 1849, the Department had cut transportation costs on all routes — horseback, stage, steamboat and railroad — by 17%. Star routes were largely responsible for the savings as contractors switched to horseback. Contractors had to be at least 16 years old. They were bonded and took an oath of office. From 1802 to 1859, postal laws required carriers to be free white persons. The typical four-year contract did not provide payment for missed trips, regardless of weather conditions. Regular schedules made carriers easy targets for thieves, though criminal punishment was harsh. Anyone found guilty of robbing carriers could receive 5 – 10 years of hard labor for the first offense and death for the second. Meanwhile, some carriers faced the hazards of snow, avalanches, ice packs, cliff-hugging roads, seas of mud, and dangerous waters. Contractors provided their own equipment. Most star route carriers traveled by horse or horse-drawn vehicle until the early 20th century. Boats, sleds, snowshoes, and skis also were used.

Free city delivery: Before 1863, postage paid only for the delivery of mail from post office to post office. Citizens picked up their mail, although in some cities they could pay an extra 2¢ fee for letter delivery or use private delivery firms. An Act of Congress effective July 1, 1863, provided that free city delivery be established at post offices where income from local postage was more than enough to pay all expenses of the service. For the first time, Americans had to put street addresses on their letters. By one year later, free city delivery had been established in 65 cities nationwide, with 685 carriers delivering mail in cities such as Baltimore, Boston, Brooklyn, Chicago, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Detroit, New York, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, St. Louis, and Washington, D.C. Postmasters, groups of citizens, or city authorities could petition the Post Office Department for free delivery service if their city met population or postal revenue requirements. The city had to provide sidewalks and crosswalks, ensure that streets were named and lit, and assign numbers to houses. Initially, carriers hand-delivered mail to customers. If a customer did not answer the carrier’s knock, ring, or whistle, the mail remained in the carrier’s satchel to be redelivered when the customer was home.

Rural free delivery (RFD): In 1890, nearly 41 million people — 65% of the population — lived in rural areas. Although many city dwellers had enjoyed free home delivery since 1863, rural citizens had to pick up their mail at the post office. Postmaster General John Wanamaker, who served from 1889 to 1893, was a merchant who became one of the most innovative and energetic people ever to lead the Post Office Department. He thought it made more sense to have one person deliver mail than to have 50 people ride into town to collect their mail for many reasons. He proposed that rural customers receive free delivery. Funding for such a scheme nationwide was not forthcoming, but in 1899, the Post Office Department decided to experiment with extending RFD across an entire county in Carroll County, Maryland. County-wide delivery proved viable. Judged a success, rural free delivery became a permanent service effective July 1, 1902. Slowly but steadily, rural free delivery spread nationwide. It stimulated road improvement, since passable roads were a prerequisite for establishing new delivery routes. Rural carriers supplied their own transportation — from horses and buggies to bicycles, motorcycles, and automobiles — to deliver the mail. They were allowed to use automobiles on their routes as early as 1907, where roads and topography permitted. Until the Post Office Department standardized specifications for rural mailboxes, a variety of boxes and containers were used. Farmers helped by putting out boxes for the rural carriers — everything from lard pails and syrup cans to old apple, soap, and cigar boxes. Rural delivery continues today to provide a vital link between urban and rural America and other parts of the world.

Airmail: The Post Office Department’s most extraordinary role in transportation was probably played in the sky. The U.S. government had been cautious in exploring the airplane’s potential. In 1905, the War Department considered three separate offers by Orville and Wilbur Wright to share their scientific discoveries on flight, then declined for budgetary reasons. Although by 1908 the Wright brothers had convinced many European nations that flight was feasible, the U.S. government owned only one airplane, and that crashed. The Post Office Department, however, was intrigued with the possibility of carrying mail through the skies and authorized its first experimental mail flight at an aviation meet on Long Island in New York in 1911. Earle Ovington, sworn in as a mail carrier by Postmaster General Frank Hitchcock, made daily flights between Garden City Estates and Mineola, New York, dropping his mail bags from the plane to the ground where they were picked up by the Mineola postmaster. Later, in 1911 and 1912, the Department authorized another 31 experimental flights at fairs, carnivals, and air meets in more than 16 states. In 1918, Congress appropriated $100,000 to establish experimental airmail routes. The Post Office Department began scheduled airmail service between New York and Washington, D.C., May 15, 1918, an important date in commercial aviation. Simultaneous takeoffs were made from Washington’s Polo Grounds and from Belmont Park, Long Island, both trips by way of Philadelphia. During the first three months of operation, the Post Office Department used Army pilots and six Army Curtiss JN-4H (“Jenny”) training planes. On August 12, 1918, the Department took over all phases of airmail service, using newly hired civilian pilots and mechanics and six specially built mail planes from the Standard Aircraft Corporation. These early mail planes had no instruments, radios, or other navigational aids. Pilots flew by dead reckoning. Forced landings occurred frequently due to bad weather, but fatalities in those early months were rare, largely because of the planes’ small size, maneuverability, and slow landing speed.

The Post Office Department issued its first postage stamps on July 1, 1847. Previously, letters were taken to a post office, where the postmaster would note the postage in the upper right corner. The postage rate was based on the number of sheets in the letter and the distance it would travel. Postage could be paid in advance by the writer, collected from the addressee on delivery, or paid partially in advance and partially upon delivery.

In 1837, Great Britain’s Sir Rowland Hill had proposed a uniform rate of postage for mail going anywhere in the British Isles and prepayment by using envelopes with preprinted postage or adhesive labels. On May 6, 1840, the stamp that became known as the Penny Black, covering the one-penny charge for half-ounce letters sent anywhere in the British Isles, became available in postal facilities.

Alexander M. Greig’s City Despatch Post, a private New York City carrier, issued the first adhesive stamps in the United States on February 1, 1842. The Post Office Department bought Greig’s business and continued use of adhesive stamps to prepay postage. After U.S. postage rates were standardized in 1845, New York City Postmaster Robert H. Morris, along with postmasters in other states, provided special stamps or markings to indicate prepayment of postage. These now are known as Postmasters’ Provisionals.

On March 3, 1847, Congress authorized United States postage stamps. The first general issue postage stamps went on sale in New York City, July 1, 1847. One, priced at 5¢, depicted Benjamin Franklin. The 10¢ pictured George Washington. Clerks used a knife or scissor to cut the stamps from pregummed, unperforated sheets. Only Franklin and Washington appeared on stamps until 1856, when a 5¢ stamp honoring Thomas Jefferson was issued. A 2¢ Andrew Jackson stamp was added in 1863. George Washington has appeared on more U.S. postage stamps than any other person, followed by Abraham Lincoln. Until government-issued stamps became obligatory January 1, 1856, other postage payment methods remained legal.

In 1893, the first U.S. commemorative stamps, honoring that year’s World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, were issued. The subject — Columbus’ voyages to the New World — and size of the stamps were innovative. Standard sized stamps were too small for engraved reproductions of paintings that portrayed events connected to Columbus’ voyages. The stamps were 7/8 inches high by 1 11/32 inches wide, nearly double the size of previous stamps. Over the years, commemorative stamps have been produced in many sizes and shapes, with the first triangular postage stamp issued in 1997 and the first round stamp in 2000. The first regular issue stamp honoring an American woman was the 8¢ Martha Washington stamp of 1902. The first to honor a Hispanic American was the $1 Admiral David Farragut stamp in 1903. Native Americans were portrayed in a general way on several earlier stamps, but the first to feature a specific individual was 1907’s 5¢ stamp honoring Pocahontas. In 1940, a 10¢ stamp commemorating Booker T. Washington became the first to honor an African American. Other firsts include the 1993 29¢ stamp featuring Elvis Presley. The public was invited to vote for the “young” or the “older” Elvis for the stamp’s design. Youth triumphed, and this has become the best-selling U.S. commemorative stamp to date.

Stamp booklets were first issued April 16, 1900. They contained 12, 24, or 48 2¢ stamps. Parafinned (waxed) paper was placed between sheets of stamps to keep them from sticking together. The books had light cardboard covers printed with information about postage rates.

The first coil (roll) stamps were issued on February 18, 1908, in response to business requests. Coils were also used in stamp vending equipment. The Department hoped to place vending machines in post office lobbies to provide round-the-clock service without extra labor costs in man hours. Machines were also planned for hotels, train stations, newsstands, and stores. Twenty-five different vending machines were tested, with six chosen for tests in the Baltimore, Minneapolis, New York, Washington, D.C., and Indianapolis Post Offices. Both coil stamps and imperforate sheets were produced for vending machines, receiving a variety of distinctive perforations and separations.

The history of the United States postal system is an ongoing story of depth and breadth, rooted in a single principle: that every person in the United States has the right to equal access to secure, efficient, and affordable mail service. Above all, the history of the United States, our prominent figures and technological advances are illustrated on our postage stamps.

U.S. postal authorities have seized upon and investigated new ways to improve service always — mail distribution cases in the 18th century; steamboats, trains, and automobiles in the 19th century; planes, letter sorting machines, and automation in the 20th century and beyond.

Stamp Collecting can be challenging and rewarding at the same time. Our job is to make you feel comfortable and prideful about your collections.

CONTACT USCopyright (c) MiniatureArtWorksUSA.com - All Rights Reserved.